WELCOME TO THE

RMS TITANIC PAGE!

R.M.S. TITANIC

WHITE STAR MOMENTS

INFORMATION & GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

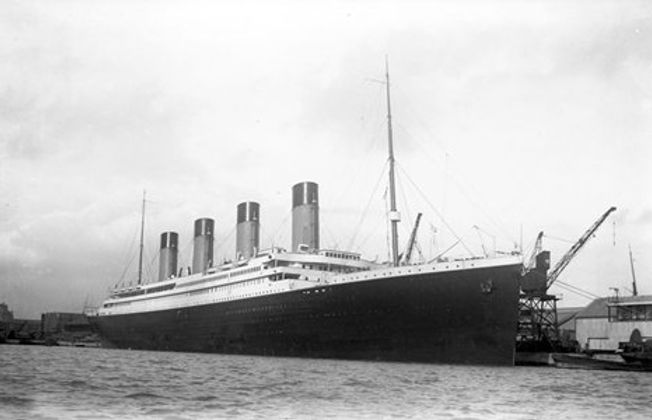

Builder: Harland and Wolff in Belfast

Laid down: 31 March 1909

Yard number: 401

Completed: 2 April 1912

Maiden voyage: 10 April 1912

Fate: Hit Iceberg and sunk on maiden voyage.

Tonnage: 46,328 tons

Length: 882 ft 9 in (269.1 m)

Beam: 92 ft 0 in (28.0 m)

Draught: 34 ft 7 in (10.5 m)

Decks: 10 decks Speed: 24 knots (maximum)

Capacity: 2,435 passengers + 892 crew

WHITE STAR MOMENTS

WHITE STAR MOMENTS

WHITE STAR MOMENTS

Built in Belfast, Ireland, in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (as it then was), the RMS Titanic was the second of the three Olympic-class ocean liners—the first was the RMS Olympic and the third was the HMHS Britannic. They were by far the largest vessels of the British shipping company White Star Line's fleet, which comprised 29 steamers and tenders in 1912. The three ships had their genesis in a discussion in mid-1907 between the White Star Line's chairman, J. Bruce Ismay, and the American financier J. P. Morgan, who controlled the White Star Line's parent corporation, the International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMM).

The White Star Line faced a growing challenge from its main rivals Cunard, which had just launched the Lusitania and the Mauretania—the fastest passenger ships then in service—and the German lines Hamburg America and Norddeutscher Lloyd. Ismay preferred to compete on size rather than speed and proposed to commission a new class of liners that would be bigger than anything that had gone before as well as being the last word in comfort and luxury. The company sought an upgrade in their fleet primarily in response to the Cunard giants but also to replace their oldest pair of passenger ships still in service, being the SS Teutonic of 1889 and SS Majestic of 1890. Teutonic was replaced by Olympic while Majestic was replaced by Titanic. Majestic would be brought back into her old spot on White Star's New York service after Titanic's loss.

The ships were constructed by the Belfast shipbuilders Harland and Wolff, who had a long-established relationship with the White Star Line dating back to 1867. Harland and Wolff were given a great deal of latitude in designing ships for the White Star Line; the usual approach was for the latter to sketch out a general concept which the former would take away and turn into a ship design. Cost considerations were relatively low on the agenda and Harland and Wolff was authorised to spend what it needed on the ships, plus a five percent profit margin. In the case of the Olympic-class ships, a cost of £3 million for the first two ships was agreed plus "extras to contract" and the usual five percent fee.

Harland and Wolff put their leading designers to work designing the Olympic-class vessels. The design was overseen by Lord Pirrie, a director of both Harland and Wolff and the White Star Line; naval architect Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland and Wolff's design department; Edward Wilding, Andrews' deputy and responsible for calculating the ship's design, stability and trim; and Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard's chief draughtsman and general manager. Carlisle's responsibilities included the decorations, equipment and all general arrangements, including the implementation of an efficient lifeboat davit design.

On 29 July 1908, Harland and Wolff presented the drawings to J. Bruce Ismay and other White Star Line executives. Ismay approved the design and signed three "letters of agreement" two days later authorising the start of construction. At this point the first ship—which was later to become Olympic—had no name, but was referred to simply as "Number 400", as it was Harland and Wolff's four hundredth hull. Titanic was based on a revised version of the same design and was given the number 401.

All three of the Olympic-class ships had ten decks (excluding the top of the officers' quarters), eight of which were for passenger use. From top to bottom, the decks were:

-

The Boat Deck

-

A deck, The promenade deck.

-

B deck, The bridge deck.

-

C deck, The shelter deck.

-

D deck, The saloon deck.

-

E deck, The upper deck.

-

F deck, The middle deck.

-

G deck, The lower deck.

-

The Orlop Decks and the Tank Top were on the lowest level of the ship, below the waterline. The orlop decks were used as cargo spaces, while the Tank Top—the inner bottom of the ship's hull—provided the platform on which the ship's boilers, engines, turbines and electrical generators were housed. This area of the ship was occupied by the engine and boiler rooms, areas which passengers would not be permitted to see. They were connected with higher levels of the ship by flights of stairs; twin spiral stairways near the bow provided access up to D Deck.

Acomodations:

-

First Class: 735

-

Second Class: 675

-

Third Class: 1,030

-

Crew: 860

-

The Olympic was capable of carrying about 3,300 people in total.

The sheer size of Titanic and her sister ships posed a major engineering challenge for Harland and Wolff; no shipbuilder had ever before attempted to construct vessels this large. The ships were constructed on Queen's Island, now known as the Titanic Quarter, in Belfast Harbour. Harland and Wolff had to demolish three existing slipways and build two new ones, the biggest ever constructed up to that time, to accommodate the giant ships. Their construction was facilitated by an enormous gantry built by Sir William Arrol & Co., a Scottish firm responsible for the building of the Forth Bridge and London's Tower Bridge. The Arrol Gantry stood 228 feet (69 m) high, was 270 feet (82 m) wide and 840 feet (260 m) long, and weighed more than 6,000 tons. It accommodated a number of mobile cranes. A separate floating crane, capable of lifting 200 tons, was brought in from Germany.

The construction of Titanic and Olympic took place virtually in parallel, with Olympic's hull laid down first on 16 December 1908 and Titanic's on 31 March 1909. Both ships took about 26 months to build and followed much the same construction process. They were designed essentially as an enormous floating box girder, with the keel acting as a backbone and the frames of the hull forming the ribs. At the base of the ships, a double bottom 5 feet 3 inches (1.60 m) deep supported 300 frames, each between 24 inches (61 cm) and 36 inches (91 cm) apart and measuring up to about 66 feet (20 m) long. They terminated at the bridge deck (B Deck) and were covered with steel plates which formed the outer skin of the ships.

The 2,000 hull plates were single pieces of rolled steel, mostly up to 6 feet (1.8 m) wide and 30 feet (9.1 m) long and weighing between 2.5 and 3 tons. Their thickness varied from 1 inch (2.5 cm) to 1.5 inches (3.8 cm). The plates were laid in a clinkered (overlapping) fashion from the keel to the bilge. Above that point they were laid in the "in and out" fashion, where strake plating was applied in bands (the "in strakes") with the gaps covered by the "out strakes", overlapping on the edges. Steel welding was still in its infancy so the structure had to be held together with over three million iron and steel rivets which by themselves weighed over 1,200 tons. They were fitted using hydraulic machines or were hammered in by hand. In the 1990s some material scientists concluded that the steel used for the ship was subject to being especially brittle when cold, and that this brittleness exacerbated the impact damage and hastened the sinking. It is believed that, by the standards of the time, the steel's quality was good, not faulty, but that it was inferior to what would be used for shipbuilding purposes in later decades, owing to advances in the metallurgy of steelmaking.

One of the last items to be fitted on Titanic before the ships launch was her two side anchors and one centre anchor. The anchors themselves were a challenge to make with the centre anchor being the largest ever forged by hand and weighing nearly sixteen tons. Twenty Clydesdale draught horses were needed to haul the centre anchor by wagon from the Noah Hingley & Sons Ltd forge shop in Netherton, near Dudley, United Kingdom to the Dudley railway station two miles away. From there it was shipped by rail to Fleetwood in Lancashire before being loaded aboard a ship and sent to Belfast.

The work of constructing the ships was difficult and dangerous. For the 15,000 men who worked at Harland and Wolff at the time, safety precautions were rudimentary at best; a lot of the work was dangerous and was carried out without any safety equipment like hard hats or hand guards on machinery. As a result, deaths and injuries were to be expected. During Titanic's construction, 246 injuries were recorded, 28 of them "severe", such as arms severed by machines or legs crushed under falling pieces of steel. Six people died on the ship herself while she was being constructed and fitted out, and another two died in the shipyard workshops and sheds. Just before the launch a worker was killed when a piece of wood fell on him.

Titanic was launched at 12:15 p.m. on 31 May 1911 in the presence of Lord Pirrie, J. Pierpoint Morgan, J. Bruce Ismay and 100,000 onlookers. 22 tons of soap and tallow were spread on the slipway to lubricate the ship's passage into the River Lagan. In keeping with the White Star Line's traditional policy, the ship was not formally named or christened with champagne. The ship was towed to a fitting-out berth where, over the course of the next year, her engines, funnels and superstructure were installed and her interior was fitted out.

Although Titanic was virtually identical to the class's lead ship Olympic, a few changes were made to differentiate the two ships. The most noticeable of these was that Titanic (and the third vessel in class Britannic) had a steel screen with sliding windows installed along the forward half of the A Deck promenade. This was installed as a last minute change at the personal request of Bruce Ismay, and was intended to provide additional shelter to first class passengers. These changes made Titanic marginally heavier than her sister, and thus she could claim to be the largest ship afloat. The work took longer than expected due to design changes ordered by Ismay and a temporary pause in work occasioned by the need to repair Olympic, which had been in a collision in September 1911. Had Titanic been finished earlier, she might well have missed her collision with an iceberg.

Titanic's sea trials began at 6 a.m. on Tuesday, 2 April 1912, just two days after her fitting out was finished and eight days before she was due to leave Southampton on her maiden voyage. The trials were delayed for a day due to bad weather, but by Monday morning it was clear and fair. Aboard were 78 stokers, greasers and firemen, and 41 members of crew. No domestic staff appear to have been aboard. Representatives of various companies travelled on Titanic 's sea trials, Thomas Andrews and Edward Wilding of Harland and Wolff and Harold A. Sanderson of IMM. Bruce Ismay and Lord Pirrie were too ill to attend. Jack Phillips and Harold Bride served as radio operators, and performed fine-tuning of the Marconi equipment. Francis Carruthers, a surveyor from the Board of Trade, was also present to see that everything worked, and that the ship was fit to carry passengers.

The sea trials consisted of a number of tests of her handling characteristics, carried out first in Belfast Lough and then in the open waters of the Irish Sea. Over the course of about twelve hours, Titanic was driven at different speeds, her turning ability was tested and a "crash stop" was performed in which the engines were reversed full ahead to full astern, bringing her to a stop in 850 yd (777 m) or 3 minutes and 15 seconds. The ship covered a distance of about 80 nautical miles (92 mi; 150 km), averaging 18 knots (21 mph; 33 km/h) and reaching a maximum speed of just under 21 knots (24 mph; 39 km/h).

On returning to Belfast at about 7 p.m., the surveyor signed an "Agreement and Account of Voyages and Crew", valid for twelve months, which declared the ship seaworthy. An hour later, Titanic left Belfast again—as it turned out, for the last time—to head to Southampton, a voyage of about 570 nautical miles (660 mi; 1,060 km). After a journey lasting about 28 hours she arrived about midnight on 4 April and was towed to the port's Berth 44, ready for the arrival of her passengers and the remainder of her crew.

On April 4 1912, Titanic arrived at Southampton at 12:40 am. Assisted by five tugs the new White Star liner was directed into the White Star Dock and tied up alongside berth No. 44. Due to a coal strike and the difficult and dirty task of transferring bunker coal from other vessels into Titanic and the time required to clean the vessel, it was decided not to open her for public inspection as was the custom before a first voyage. Instead she was dressed overall with signal flags for the benefit of the people of Southampton.

It was previously believed Titanic was dressed overall on the following day (Good Friday, 5 April), however, recent research has uncovered a contemporary note written by one of the ship’s officers confirming the date was in fact April 4.

The Board of Trade in London issued Titanic with a Passenger Certificate, good for one year. On this form Captain Edward John Smith (Certificate of Competency No. 14102) was listed as Master in replacement of Captain H. J. Haddock who had been relived in Belfast.

Titanic was certified as an emigrant ship to carry the following:

1st Class - 905

2nd Class - 564

3rd Class - 1,134

Crew - 944

Total Passengers and Crew - 3,547*

Boats and lifesaving appliances were detailed as follows:

14 lifeboats of an aggregate capacity of 9,172 cubic feet and capable of accommodating 915 persons.

2 boats (emergency type) of an aggregate capacity of 648 cubic feet and capable of accommodating 64 persons.

4 collapsible boats capable of accommodating 188 persons.

3,560 lifebelts and 48 lifebuoys were carried.

With a full passenger load (3,547) there was only accommodation in the available boats for 1,167 persons, or just over one third of those onboard.

*it was noted on this form that ‘On any voyage on which this vessel may be cleared as an emigrant ship, the number of passengers is governed by the certificate granted by the emigration officer for that voyage, and not by this certificate.’

Captain Edward Smith was still in command of Olympic at the time of the incident. One crew member, Violet Jessop, survived not only the collision with the Hawke but also the later sinking of Titanic and the 1916 sinking of Britannic.

At the subsequent inquiry the Royal Navy blamed Olympic for the incident, alleging that her large displacement generated a suction that pulled Hawke into her side.The Hawke incident was a financial disaster for Olympic's operator. A legal argument ensued which decided that the blame for the incident lay with Olympic, and although the ship was technically under the control of the pilot, the White Star Line was faced with large legal bills and the cost of repairing the ship, and keeping her out of revenue service made matters worse. However, the fact that Olympic endured such a serious collision and stayed afloat, appeared to vindicate the design of the Olympic-class liners and reinforced their "unsinkable" reputation.

On the 5th Titanic's maiden voyage was just five days away and crews were busy getting her ready as her holds were filled with not only cargo for New York, but also tons of supplies to be used on board ship during the crossing. On the picture below, hundreds of bottles of beer, supplied by C.C.Hibbert & Co, as they were made ready to be removed from the goods sheds alongside the White Star Line berths #43 and #44.

The following day (April 6th) White Star Line recruited the final number of crew required for the Titanic's maiden voyage to New York. The recruitment process took place in the union hiring halls in Southampton. Following the prolonged coal strike which forced many vessels to be laid up at the port, many crewmen after a forced period of unemployment, were anxious to join the new vessel.

On April 7th the Titanic remained tied up at Berth 44. The coal strike had ended on the previous day (April 6) but there was not enough time for newly mined coal to be shipped to Southampton and loaded on Titanic. Coal from five International Merchant Marine (owner's of the Titanic) ships in port and leftover coal from her sister ship Olympic had rumbled down into Titanic's spacious coal bunkers. She had arrived with 1,880 tons of coal, and to this was added 4,427 tons while in Southampton. The week in port consumed 415 tons for steam to operate cargo winches and to provide light and heat throughout the ship. The waterfront was deserted on this Easter Sunday (April 7, 1912), and all work aboard the Titanic had ceased for the day. No smoke or steam rose from her funnels. The ship's bell rang across the harbor marking the passing hours and her Blue Ensign

fluttered at her stern flagstaff. It was the last quiet hours Titanic would ever know.

April 9th was Titanic's final full day at Southampton. The following day she would begin her maiden voyage. Food and stores continued to be taken on board. Captain Clark, the Board of Trade surveyor, was on board inspecting just about every part of the ship. According to the Second Officer Charles Lightoller "he did his job, and I'll certainly say he did it thoroughly". Captain E.J. Smith, Titanic's Commander, performed his own inspections. While he was visiting the bridge, a London photographer took his picture. The photograph gained immortality as the only picture every taken of 'E.J.' on the bridge of his largest, and last, command. Thomas Andrews stopped to rest and wrote to Mrs. Andrews: "The Titanic is now about complete and will I think do the old Firm credit tomorrow when we sail". All of the officers, except Smith, spent the night on board, keeping regular watches and supervising the final night in port.

At noon on the 10 April 1912 the Titanic set sail from Southampton, 922 passengers were recorded as having embarked Titanic at Southampton. Immediately, there was a potential disaster. There was a near collision with the steamer New York. The New York being much smaller than the Titanic was sucked in to her wake as the Titanic giant triple screw propellers rotated. The New York's mooring snapped and was dragged towards the port side of her. This is exactly what happened to her sister ship when she collided with the HMS Hawke.

Titanic's passengers numbered around 1,317 people: 324 in First Class, 284 in Second Class. and 709 in Third Class. Of these, 869 (66%) were male and 447 (34%) female. There were 107 children aboard, the largest number of which were in Third Class. The ship was considerably under capacity on her maiden voyage, as she could accommodate 2,566 passengers—1,034 First Class, 510 Second Class, and 1,022 Third Class.

Usually, a high prestige vessel like Titanic could expect to be fully booked on its maiden voyage. However, a national coal strike in the UK had caused considerable disruption to shipping schedules in the spring of 1912, causing many crossings to be cancelled. Many would-be passengers chose to postpone their travel plans until the strike was over. The strike had finished a few days before Titanic sailed; however, that was too late to have much of an effect. Titanic was able to sail on the scheduled date only because coal was transferred from other vessels which were tied up at Southampton, such as City of New York and Oceanic as well as coal Olympic had brought back from a previous voyage to New York and which had been stored at the White Star Dock.

Some of the most prominent people of the day booked a passage aboard Titanic, travelling in First Class. Among them were the American millionaire John Jacob Astor IV and his wife Madeleine Force Astor, industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim, Macy's owner Isidor Straus and his wife Ida, Denver millionairess Margaret "Molly" Brown, Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and his wife, couturière Lucy (Lady Duff-Gordon), cricketer and businessman John Borland Thayer with his wife Marian together with their son Jack, the Countess of Rothes, author and socialite Helen Churchill Candee, journalist and social reformer William Thomas Stead, author Jacques Futrelle with his wife May, and silent film actress Dorothy Gibson, among others. Titanic's owner J. P. Morgan was scheduled to travel on the maiden voyage, but cancelled at the last minute. Also aboard the ship were the White Star Line's managing director J. Bruce Ismay and Titanic's designer Thomas Andrews, who was on board to observe any problems and assess the general performance of the new ship.

The exact number of people aboard is not known as not all of those who had booked tickets made it to the ship; about fifty people cancelled for various reasons, and not all of those who boarded stayed aboard for the entire journey. Fares varied depending on class and season. Third Class fares from London, Southampton or Queenstown cost £7 5s (equivalent to £641 today) while the cheapest First Class fares cost £23 (£2,034 today). The most expensive First Class suites were to have cost up to £870 in high season (£76,929 today).

Titanic arrived at Cherbourg at 6.35pm. Fifteen 1st and nine 2nd Class passengers disembarked after making the cross channel passage. 142 1st, 30 2nd and 102 3rd Class passengers embarked at the French port for New York by the passenger/baggage tenders Nomadic and Traffic. Titanic departed at 8.10pm for Queenstown, Ireland.

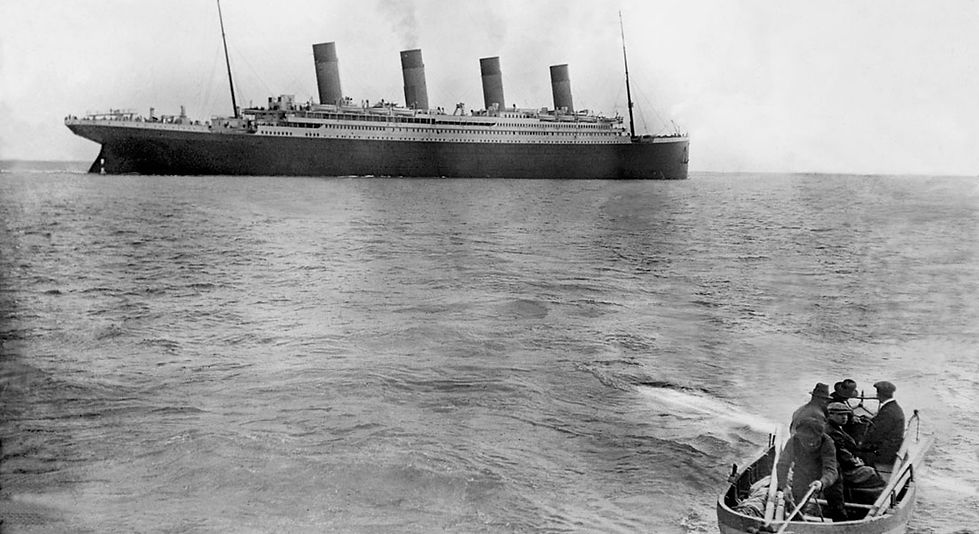

The following day at 11:30am Titanic anchored off Roches Point at the entrance to Cork Harbour. Seven 1st Class passengers disembarked and seven 2nd and 113 3rd Class passengers embarked from the tenders Ireland and America. One crewman, Fireman John Coffey a native of Queenstown, desserts the ship. At 1.30pm Titanic departed Queenstown. Onboard are an estimated 1,316 passengers, representing about one-half of the ships total passenger capacity on what was classed as low-season on the North Atlantic.

The picture below, from Titanic Belfast's website was taken by theological student Francis Brown as he left the ship, and is one of the last-ever photographs of Titanic before she sank.

Between April 11 and 12, Titanic covered 386 miles in fine, calm, clear weather. Each day, as the voyage went on, everybody's admiration of the ship increased: for the way she behaved; for the total absence of vibration; for her steadiness even with the ever-increasing speed. As Lightoller observed "we were not out to make a record passage; in fact the White Star Line invariably run their ships at reduced speed for the first few voyages". Lawrence Beesley would remark that the wind was rather cold, generally too cold to sit out on deck to read or write, so many spent a good deal of the time in the library. Beesley also remarked to the way Titanic listed to port. The purser explained that likely coal had been used mostly from the starboard side. This excess starboard coal consumption was due to the fire which had burned continuously in boiler room number 6 since Titanic's sea trials almost two weeks earlier, but by Friday had been almost brought under control. During the day, Titanic had received many wireless messages of congratulations and good wishes including those from the Empress of Britain and La Touraine. Each greeting had also contained advice of ice, but this was not uncommon for an April crossing. Late in the evening, Titanic's wireless apparatus ceased to function, forcing Phillips and Bride to work through the early morning hours to trouble shoot the apparatus and locate the problem. As Friday passed into Saturday, vessels were encountering ice all along the North Atlantic shipping lanes.

Between noon Friday and noon Saturday, Titanic covered 519 miles. At 10:30 a.m. Captain Smith began the daily inspection. During the engine room inspection, Chief Engineer Bell advises Smith that the fire in boiler room 6 has finally been extinguished. However the bulkhead which forms part of the coal bunkers showed some signs of heat damage and one of the firemen was ordered to rub oil onto the damaged areas. Deep down in the stokeholds, the 'black gang', stripped to the waist, continued to meet the harsh demands of the furnaces in an atmosphere thick with coal dust. It was hard to realize, in the terrific heat of the stokehold, that up on deck it was nearly freezing. Hour and after hour, watch after watch, the merciless back-breaking labor continued.

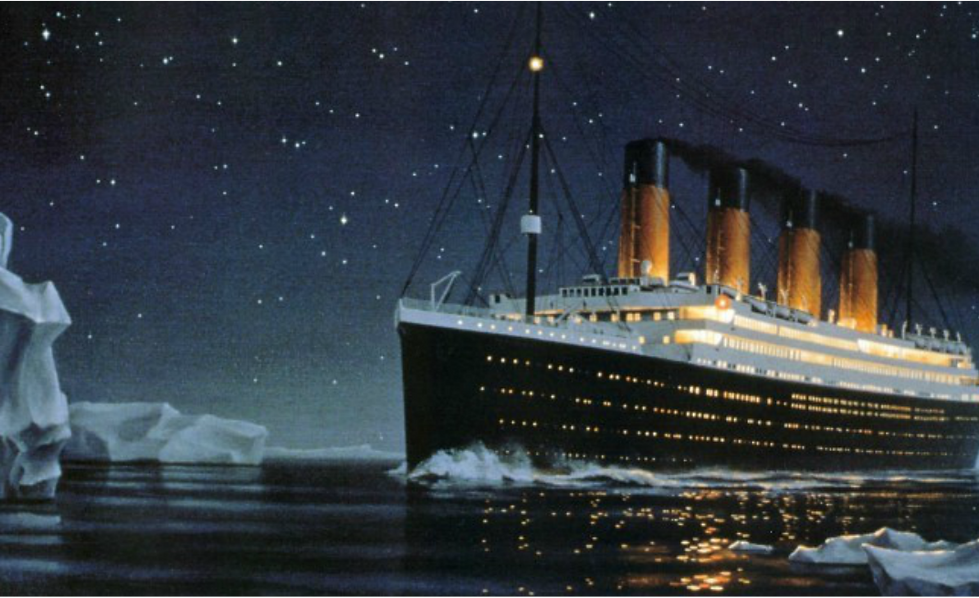

The fine weather continued with a smooth sea and a moderate south-westerly wind. Everyone was in good spirits. The hardier passengers paced briskly up and down the Boat Deck, even though the breeze was chilly but invigorating. Between Saturday and Sunday, the Titanic covered 546 miles. Earlier, Titanic had picked up a wireless message from the Caronia warning of ice ahead, followed by a message from the Dutch liner Noordam, again warning of "much ice" ahead. In the early afternoon, the Baltic reported "large quantities of field ice" about 250 miles ahead of the Titanic (this is the message which Smith eventually gives to J. Bruce Ismay). A short time later, the German liner Amerika warned of a "large iceberg" but this message was not sent to the bridge. Just before 6:00 pm Smith alters the ship's course slightly to south and west of its normal course, perhaps as a precaution to avoid the ice warned by so many ships. Titanic's course is now South 86 West true. But no orders were given to decrease speed, in fact at this time, Titanic's speed was actually increasing. At 7:30 pm, 3 warning messages concerning large icebergs were intercepted from the Californian indicating that ice is now only 50 miles ahead. After excusing himself from Dinner, Smith heads for the bridge where he discusses the unusually calm and clear conditions with 2nd Officer Lightoller. Around 9:20 pm Smith retired for the night with the usual order to rouse him "if it becomes at all doubtful" after which Lightoller cautions the lookouts to watch carefully for ice until morning. At 9:40 pm, a heavy ice pack and iceberg warning was received from the Mesaba. This message was overlooked by Bride and Phillips due to their preoccupation with passenger traffic. Altogether the many ice warnings received this day show a huge ice field 78 miles long directly ahead of Titanic.

By 10:00 pm Lightoller was relieved by 1st Officer Murdoch. At 10:55 pm, some 10-19 miles north of Titanic, the Californian was stopped in ice and sends out warnings to all ships in area. Bride rebukes the Californian with the famous reply "Keep out! Shut up! You're jamming my signal. I'm working Cape Race" and the Californian wireless officer shuts down his set for the night. By this time, 24 of 29 boilers were fired and the Titanic was now running at over 22 knots, the highest speed she had ever achieved.

At 11:30 pm, lookouts Fleet and Lee noted a slight haze appearing directly ahead. At 11:40 pm with the Titanic steaming at over 22 knots, Fleet saw a large iceberg dead ahead and signals the bridge. Sixth Officer Moody acknowledges the signal and relays the message to Murdoch who instinctively orders "Hard-a-starboard" and telegraphs the engine room to stop all engines, followed by full astern. He also closes the watertight doors. Titanic slowly begins to veer to port, but an underwater spar from the passing berg scraps and bumps along the starboard side forward for a 300-foot distance fully opening five forward compartments to the sea, as well as flooding the coal bunker servicing the No. 9 stokehold. By 11:55 pm, 15 minutes after the collision, the post office on "G" Deck forward was already flooding. After a quick inspection of the damage by Wilde, Boxhall and Andrews, Smith knew the worst...that Titanic was sinking and the more than 2,200 people on board were in extreme peril. With a heavy heart, Smith personally took Titanic's position, worked out by 4th Officer Boxhall, to the wireless room. Handing the paper to Phillips shortly after midnight, he ordered a call for assistance. Phillips taped out the regulation distress signal CQD...MGY...CQD...MGY...

Shortly after midnight, the Squash court, 32 feet above keel, was awash. The majority of the boilers had been shut down, and huge clouds of steam roared out of the relief pipes secured to the sides of the funnels. Smith ordered the lifeboats to be uncovered and mustered the crew and passengers. There was only enough room for 1,178 people out of an estimated 2,227 on board, if every boat was filled to capacity. Between 12:10 am and 1:50 am, several crew members on Californian saw what is thought to be a tramp steamer's lights. Rockets were also observed, but no great concern was taken. Numerous ships have heard the Titanic's wireless distress signals and many were on their way to assist, including the Cunard liner Carpathia, under the command of Arthur Rostron some 58 miles southeast of the Titanic's position. At 12:15 am, Wallace Hartley and his band began to play lively ragtime tunes in the 1st Class lounge on "A" Deck. They would continue to almost the end, and every member of the band would be lost.

At 12:25 am Smith gave the order to start loading lifeboats with women and children, and this order was particularly followed to the letter by 2nd Officer Lightoller. By 12:45 am, starboard lifeboat No. 7 was safely lowered away with only 28 people, while it could carry 65. At about this same time, the first distress rocket was fired by Quartermaster George Rowe, under the direction of Boxhall, from the bridge rail socket on the Boat Deck by the No. 1 emergency cutter. They soared 800 feet in the air and exploded into 12 brilliant white stars, along with a loud report. Boxhall sees a vessel approach and then disappear, despite attempted to contact her via Morse lamp. By 1:15 am, water had reached Titanic's name on the bow, and she now listed to port. By that time, seven boats had been lowered, but with far fewer passengers and crew than rated capacity. The tilt of the deck grew steeper and boats now began to be more fully loaded, with starboard No. 9 lowered at 1:20 am with some 56 people aboard. The Titanic had now developed a noticeable list to starboard. By 1:30 am signs of panic begin to appear as port No. 14 was lowered with 60 people, including 5th Officer Lowe. Lowe was forced to fire three warning shots along the ship's side to keep a group of unruly passengers from jumping into the already full boat.

Wireless distress calls tapped out by Phillips reached desperation status, with messages such as, "we are sinking fast" and, "cannot last much longer". Smelting magnate Ben Guggenheim, along with his manservant Victor Giglio returned to their cabins and changed into evening dress explaining, "We've dressed up in our best and are prepared to go down like gentlemen". By 1:40 am most of the forward boats had left and passengers began to move to the stern area. J. Bruce Ismay leaved on collapsible "C" with 39 aboard, the last starboard boat to be lowered. The forward Well Deck was awash. By 2:00 am water was only 10 feet below the Promenade Deck. At about this time, Hartley chose the band's final piece 'Nearer, My God, to Thee'. Hartley had always said it would be the hymn he would select for his own funeral. With more than 1,500 still on board, and just 47 positions available in Collapsible "D", Lightoller instructed the crew to lock arms and form a circle around the boat, permitting only women and children to pass through the circle. At 2:05 am, "D" began its downward journey with 44 people out of a rated capacity of 47.

The sea was pouring on to the forward end of "A" Deck, and Titanic's tilt grew steeper. At that same time, Smith went to the wireless cabin and released Phillips and Bride telling them that they have "done their duty". On the way back to his bridge, Smith told several crewmen "It's every man for himself". His last thoughts were likely of his beloved wife Eleanor and his young daughter Helen. As Walter Lord described the scene in "A Night to Remember", "with the boats all gone, a curious calm came over the Titanic. The excitement and confusion were over and the hundreds left behind stood quietly on the upper decks. They seemed to cluster inboard, trying to keep as far away from the rail as possible". The stern began to lift clear of the water, and passengers moved further and further aft. At about 2:17 am Titanic's bow plunged under while hundreds of 2nd and 3rd Class passengers heard confession from Father Thomas Byles gathered at the aft end of the Boat Deck.

At 2:18 am a huge roar was heard as all moveable objects inside Titanic crashed towards the submerged bow. The lights blinked once and then went out, leaving Titanic visible only as a black silhouette against the starlit sky. Many were convinced that the hull broke in two between the 3rd and 4th funnels. The ship achieved a completely perpendicular position and remained there for several minutes. At 2:20 am she settled back slightly and slid down to the bed of the North Atlantic some 13,000 feet below.

Almost at once, the night was punctuated with the cries of the survivors, growing in number and anguish until in Thayer's words they became "a long continuous wailing chant". The ghastly noise continued for some time, but mercifully many would freeze to death rather than drown. The cries even affected the hardened Lightoller who heard the "heartrending, never-to-be-forgotten sounds" from overturned Collapsible "A". Later, he confessed that he had never allowed his thoughts to dwell on those terrible cries. At 3:30 am, the Carpathia's rockets were sighted by those in the lifeboats and at 4:10 am Titanic's No. 2 lifeboat was picked up. By 5:30 am, after being advised by the Frankfort of Titanic's loss, the Californian made for the disaster site and arrived about three hours later, just as the last boat, No. 12, was rescued by the Carpathia. True to form, Lightoller was the last survivor to come on board. At 8:50 am the Carpathia left the searching for survivors to other ships and headed for New York. She carried only 705 survivors. An estimated 1,522 souls were lost. J. Bruce Ismay sent the following message to the White Star Line's New York offices: "Deeply regret advise you Titanic sank this morning after collision with iceberg, resulting in serious loss of life. Full particulars later."

Carpathia arrived at Pier 34 in New York on the evening of 18 April after a difficult voyage through pack ice, fog, thunderstorms and rough seas. Some 40,000 people stood on the waterfront, alerted to the disaster by a stream of radio messages from Carpathia and other ships. Due to communications difficulties, it was only after Carpathia docked – a full three days after Titanic 's sinking – that the full scope of the disaster became public knowledge. The heaviest loss was in Southampton, home to most of the crew; 699 members of the crew gave Southampton addresses, and 549 Southampton residents, almost all crew, were lost in the disaster.

Even before Carpathia arrived in New York, efforts were getting underway to retrieve the dead. Four ships chartered by the White Star Line succeeded in retrieving 328 bodies; 119 were buried at sea, while the remaining 209 were brought ashore to the Canadian port of Halifax, Nova Scotia, where 150 of them were buried. Memorials were raised in various places – New York, Washington, Southampton, Liverpool, Belfast and Lichfield, among others – and ceremonies were held on both sides of the Atlantic to commemorate the dead and raise funds to aid the survivors. The bodies of most of Titanic 's victims were never recovered, and the only evidence of their deaths was found 73 years later among the debris on the seabed: pairs of shoes lying side by side, where bodies had once lain before eventually decomposing in the sea waters.[42]

The prevailing public reaction to the disaster was one of shock and outrage, directed against a number of issues and people: why were there so few lifeboats? Why had Ismay saved his own life when so many others died? Why did Titanic proceed into the icefield at full speed? The outrage was driven not least by the survivors themselves; even while they were aboard Carpathia on their way to New York, Beesley and other survivors determined to "awaken public opinion to safeguard ocean travel in the future" and wrote a public letter to The Times urging changes to maritime safety.

In places closely associated with Titanic, there was a deep sense of grief. Crowds of weeping women, the wives, sisters and mothers of crew members, gathered outside the White Star Line's offices in Southampton to find out what had happened to their loved ones – most of whom had perished. Churches in Belfast were packed and shipyard workers wept in the streets after the news was announced. The ship had been a symbol of Belfast's industrial achievements and there was not only a sense of grief but also of guilt, as those who had built Titanic came to feel that they had in some way been responsible for her loss.